Die Orte sind hinlänglich bekannt: touristische Epizentren, immer wieder fotografiert mit dem unhintergehbaren Wunsch nach Einschreibung und Authentizität. Üblicherweise dokumentieren die Aufnahmen ich bin da-gewesen, sollen Erfahrung beglaubigen. Diese private Gebrauchsweise der Fotografie ist Ausdruck für jenes Phänomen, das Gottfried Benn in seinem Gedicht „Reisen“ beschrieben hat: „Ach, vergeblich das Fahren! Spät erst erfahren Sie sich“. Der Wunsch nach Horizonterweiterung ist meist utopisch, es gilt wohl eher, was Susan Sontag über den Zusammenhang zweier moderner Aktivitäten, Tourismus und seinen Zwillingsbruder Fotografie, gesagt hat: Fotografieren führt häufig zu einer Form der Verweigerung von Erfahrung, die Bilder bilden eine Ersatzwirklichkeit, hinter der die Realität verschwindet.

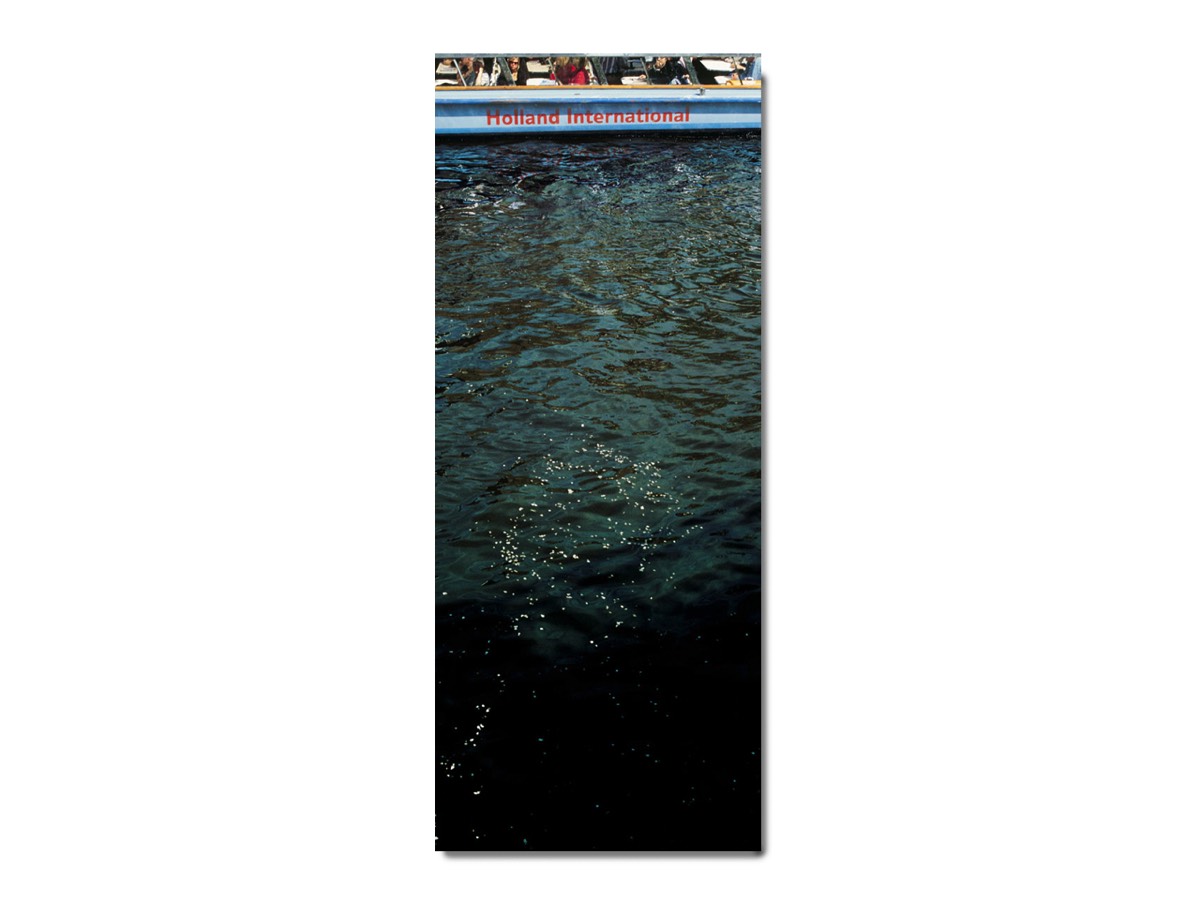

Doch mit dokumentarischem Anspruch war Architekturfotografie, die es seit Erfindung dieses Mediums gibt, einst angetreten: Die Bilder sollten die Welt vermitteln, Fernes oder Fremdes nahe bringen, die Sehnsüchte der Betrachter wecken und vergleichendes Sehen vereinfachen. In der künstlerischen Fotografie ist dieser letzte Aspekt seit den 60er Jahren des vergangenen Jahrhunderts insbesondere von Bernd und Hilla Becher betont worden, um künstlerische Aussagen zu machen. Wie jene Pioniere ist Thorsten Kern in bestimmter Hinsicht um Neutralität bemüht: Der Himmel ist in der Regel bedeckt, auf starke Farbigkeit wird verzichtet. Allerdings gibt es Ausnahmen, der Hamburger Fischmarkt etwa ist unter blauem Himmel mit weißen Wattewolken fotografiert, was insofern ungewöhnlich ist, als der touristische Blick auf ihn eher im Morgengrauen, nach nächtlichem Besuch in St. Pauli, fällt als am helllichten Tage. Ganz anders als im Becher’schen Archiv dokumentarischer Aufnahmen variiert Kern bei seiner Serie die Formate und die Blickwinkel je nach Sujet: Vom 150 x 60 cm schmalen Blick unter dem üblicherweise im Querformat erfassten Arc de Triomphe heraus bis hin zum mit 125 x 125 cm quadratischen Bild des Eiffelturms, der in diesem Ausschnitt von einer weißen, mit Schriftzügen besprühten Mauer bedrängt zu werden scheint.

Was Kerns Fotografien verbindet ist das Motiv der unorthodoxen Suche nach Randphänomenen, was zu einer Fülle interessanter Einzelbilder und einem überzeugenden Gesamtkonzept führt. Sein Blick vorbei am Zentrum lehrt uns, die Details neu zu sehen, er gibt ihnen den Raum, den sie in unserer Erfahrung haben, und indem er sie konserviert und bildwürdig macht, nimmt er Abstand von jedem Klischee. Ein bewusster Einbau grafischer Fehler wird dabei, augenzwinkernd und authentizitätsverstärkend, billigend in Kauf genommen: Den Asphalt des Potsdamer Platzes oder den Kiesboden, der auf dem Bild eines Teils des Buckingham Palace genau die Hälfte der Bildfläche ausmacht, hat man nach Besichtigung meist in ebenso starker Erinnerung wie die wahrgenommenen Gebäude

Jeder Reisende weiß, dass die steingewordenen Repräsentanten des Massentourismus, die säkularisierten Mythen, längst Opfer der Vermarktung geworden und immer wieder gut für Enttäuschungen sind, da sie ständigem Wandel und städtebaulichen Veränderungen unterliegen und ihrer Verklärung nicht gerecht werden können: Vor dem Kölner Dom stehen Mülleimer, umgeben von schlecht gezieltem Abfall, die Sagrada Familia ist nicht nur das Herzstück des spanischen Jugendstils, sondern eine 1883 begonnene, zeitweise ruhende Baustelle, und die Rückseiten mancher Gebäude scheinen in keinem Zusammenhang mit ihren repräsentativen Schauseiten zu stehen.

Durch Kerns Zugriff entstehen keine verspielten Suchbilder, sondern Blicke auf Ränder und Details, die nicht als pars-pro-toto für das stets im Titel genannte Motiv, aber als Ergebnisse eines aufmerksamen Blicks gelten können, der sich bisweilen mit den Erfahrungen der Bildbetrachter stärker deckt, als wenn eine präzise Erfassung des Ganzen stattfinden würde. Und in dieses Konzept passt der Blick auf ein in der Prinsengracht schwimmendes Körbchen, das sofort nach seinem einstigen Inhalt fragen lässt, genauso wie der Blick unter eine der wie aus dem Boden herauswachsenden Kugeln des Brüsseler Atomiums. Von einem der singulären Werke der Moderne, Frank Lloyd Wrights New Yorker Guggenheim Museum, ist nicht die legendäre Spiralform zu erkennen, die noch in Hiroshi Sugimotos schemenhafter Aufnahme den Wiedererkennungswert ausmacht. Statt der Rampe hat Kern einen Teil der Grundfläche und des Erdgeschosses, eine angeschnittene Blumenschale und den Teil des Schriftzugs erfasst, der in seiner Isolierung das Synonym eines Hauses mit allen Anklängen von Geborgenheit, das Wort HEIM, bildet. Diese Fotografie macht deutlich, dass Kern seine Aufnahmen nicht manipuliert und inszeniert, sondern innovativ und nicht ohne Ironie mit dem Vorgefundenen arbeitet.